PL2

Geopolitical Puppeteers: Identifying the Roles of Hidden Actors Shaping the Commercial Determinants of Global Health

26

Jan

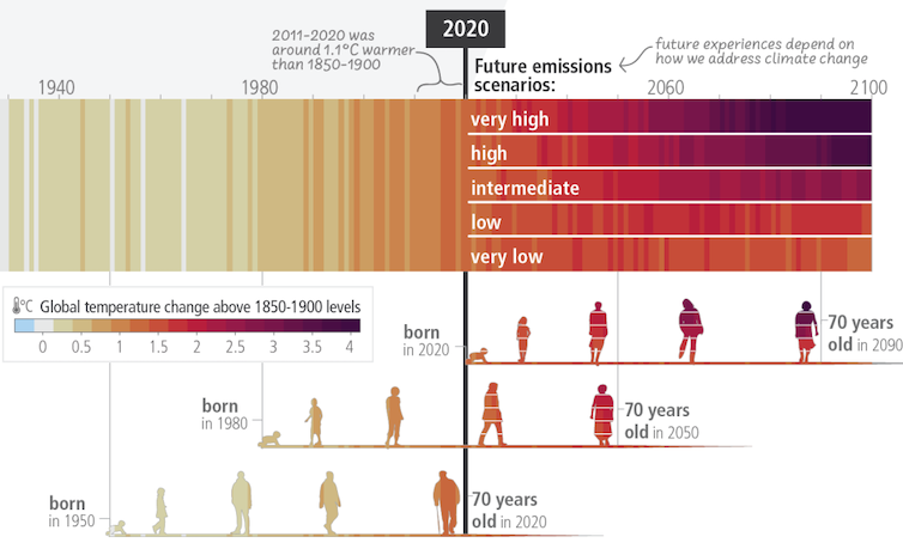

Addressing long-term issues parallels the broader impact of CDoH, extending across sectors and affecting health outcomes. Balancing short-term priorities in global governance resonates with mitigating harmful commercial practices. The integration of health within larger goals aligns with recognizing CDoH's influence on global health and well-being (6). The report prompts interdisciplinary discussions and policy development, reflecting the call to counteract CDoH's impact. Amid complex challenges, collaborative efforts among stakeholders are vital for addressing the evolving landscape (4; 6). Addressing commercial determinants of health is pivotal in light of climate crisis, promising dual benefits for the environment and health. According to the EAT- Lancet Commission report, shifts towards consuming less sugar, salt, and saturated fat, and more plant-based foods can combat climate change and enhance health (7). Advocating for sustainable, healthy food systems can mitigate climate impacts and contribute to a more sustainable future. The increasing climate damage as presented in the recent synthesis IPCC report (IPCC AR6 SYR from March 2023) accentuates the urgency of this action.

Figure 1: Climate damage is worsening faster than expected, but there’s still reason for optimism (IPCC AR6, SYR, 2023).

Figure 1: Climate damage is worsening faster than expected, but there’s still reason for optimism (IPCC AR6, SYR, 2023).

Plenary 2 aims to discuss a way forward by exploring strategies and approaches that mitigate the harmful effects of CDoH on health and instead channel their influence towards promoting fairness, equality, and the overall well-being of individuals and the planet. This requires considering geopolitical considerations and developing policies and interventions that reshape the commercial sector's practices to prioritize health and social equity. The future directions should emphasize the need for a multi-faceted approach that addresses the complex and interconnected factors that contribute to commercial determinants of health. The governments should regulate and limit commercial practices that harm public health, support practices that promote health, and promote health literacy and consumer awareness. Additionally, the need to address commercial determinants of health in conjunction with social determinants of health and promote health equity is crucial (8). The session also needs to address the banking sector plays a pivotal role in lending money to industries that have significant implications for commercial determinants of health, encompassing sectors such as fossil fuels, artificial intelligence (AI), beverage and food, and the arms industry. These financial activities have complex ties to geopolitics and can exert profound effects on public health outcomes.

Plenary 2 will identify hidden entities influencing global health, such as Multinational Corporation and lobbyists. The parallel sessions will subsequently explore these for four specific themes/industries – 1) food, beverage and agricultural industry; 2) energy producing industries; 3) “new” technologies; and 4) the arms industry. This discussion also highlights the ethical implications of these actors' influence, including health disparities and environmental harm. It will pinpoint gaps in current legislation, suggesting improvements for regulatory frameworks. By fostering public discourse, this dialogue enhances accountability, motivates responsible practices among these hidden actors, and raises public awareness about CDoH.

Key themes to be highlighted in Plenary 2

The plenary will start with an overview presentation on CDoH that will map out the challenges, and be forward-looking and action oriented. Subsequently, there will be a panel discussion on the following actors influencing commercial determinants of health:

The power of trans-national corporations (TNCs) on global and national economic policies mean that countries find it increasingly difficult to shape policies in favour of health. For example, multinational corporations (MNCs) may promote the consumption of processed foods, sugary beverages, and tobacco products in low and middle income countries (LMICs), where regulations and public health campaigns may be less robust than in more developed countries. In addition, hegemonic countries may use their economic and political power to shape international trade agreements and policies in ways that favour their own industries and interests, often at the expense of LMICs. This can include measures that make it difficult for LMICs to regulate or tax unhealthy products or that promote the export of such products to these countries.

Lobbyists play a vital role in shaping public health policies by influencing legislation in favor of their respective industries. There have been instances where lobbyists, representing industries like tobacco and alcohol, have successfully hindered or diluted health-promoting policies (9). The lobbyist from the fossil fuel industry, specifically ExxonMobil, possessed extensive knowledge about climate change, accurately predicting global warming due to fossil fuel burning and dismissing the possibility of an ice age, but instead of communicating this knowledge, they actively worked to deny it and orchestrate lobbying and propaganda campaigns to impede climate action (10).

The plenary will touch upon the four industries that hidden actors shaping impacts to CDoH.

First, the food and beverage industry. Transnational corporations and influential lobbying groups employ various strategies to shape policies and consumer choices, often prioritizing profits over public health. Aggressive marketing practices, deceptive tactics, and industry trade associations contribute to these impacts, highlighting the need for transparency, regulation, and advocacy to mitigate their negative effects on health. Food industry actors in Chile engage in various political practices, including supporting community initiatives, funding research, and lobbying against front-of-pack nutrition labelling policies and tax increases on sugar-sweetened beverages. These practices, facilitated by Chile's neo-liberal economy, have the potential to influence public health policy and require robust mechanisms to address undue corporate influence. Despite this influence, Chile has implemented a front-of-pack nutrition labelling policy (11). The tobacco industry, exemplified by Philip Morris International (PMI), has a history of using covert tactics to undermine public health efforts. PMI's Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, purportedly advocating for smoking cessation and harm reduction, has been criticized for potential industry influence and promotion of risky alternative tobacco products (12). The alcohol industry, much like tobacco, actively undermines global alcohol policies by submitting misleading claims and exerting significant influence on key initiatives like the World Health Organization's Global alcohol action plan 2022-2030. This interference, which accounted for 24% of all submissions, has resulted in weakened policies and a concerning focus shift away from evidence-based measures like the WHO's 'SAFER' initiative (alcohol initiative). Governments must resist this industry pressure to safeguard public health against the widespread harm caused by alcohol consumption (13).

Second, the fossil fuel industry, specifically the lobbyists from ExxonMobil, possessed extensive knowledge about climate change, accurately predicting global warming due to fossil fuel burning and their scientists correctly dismissing the possibility of a coming ice age, but instead of communicating this knowledge, they actively worked to deny it and orchestrate lobbying and propaganda campaigns to impede climate action (14). These actions have hindered progress in transitioning to cleaner and renewable energy sources, contributing to environmental degradation and negative health impacts associated with air pollution and climate change. Moreover, lobbying groups associated with the fossil fuel industry, such as the American Petroleum Institute (API), have been influential in shaping energy policies and regulations. The API has been involved in advocating for deregulation, promoting the expansion of fossil fuel extraction, and undermining renewable energy initiatives (15). These efforts have the potential to perpetuate the reliance on fossil fuels and hinder the necessary transitions towards sustainable energy systems.

Third, the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) holds significant geopolitical implications for global health. Countries like the United States, the European Union, and China approach AI governance differently, impacting AI's role in healthcare. AI-driven health interventions, spanning diagnosis, risk assessment, disease prediction, and policy planning, offer potential solutions in LMICs. However, ethical, regulatory, and practical considerations must be addressed swiftly to ensure equitable and responsible AI deployment. This growing geopolitical competition raises concerns about data privacy, ethics, and access to cutting-edge AI healthcare advancements. Collaborations between nations are essential to ensure the equitable distribution of AI-driven health benefits while addressing potential risks. The geopolitical landscape of AI impacts on health is a complex interplay of technological innovation, national interests, and global health considerations, demanding careful navigation and international cooperation (16;17).

Fourth, the arms industry, by contributing to conflicts and wars, leaves behind a trail of casualties, displaced people, and destroyed health infrastructure. In an indirect yet impactful way, arms manufacturers also shape global health determinants. The consequent physical, mental, and social health impacts are substantial. The ongoing conflict in Syria has caused a significant decline in oil production, leading to higher global oil prices and increased greenhouse gas emissions from alternative energy sources. The Russian aggression on Ukraine has resulted in a significant shift in global energy politics, with the EU reducing fossil fuel imports and China turning to Russia and Saudi Arabia for oil and gas. This geopolitical shift has substantial global impacts, with the war impairing wheat production and transportation (18). For further reading, see SIPRI Yearbook 2023 (https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2023)

This plenary will also identify positive impacts on population and planetary health that can result from countering the actions of the hidden actors by promoting the “mechanisms”, namely, 1) strengthening regulations and policies, 2) promoting transparency and accountability, 3) reducing conflicts of interest, 4) promoting healthier business models, and 5) empowering consumers.

For example, the increase of supermarkets that sell healthy foods and decreased dependence on convenience stores selling “junk food” in low-income areas were associated with improved diets and decreased rates of obesity (20). The availability of parks and recreational facilities was associated with increased physical activity and decreased rates of obesity (21). Industries have a significant impact on the global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change, but they also have the potential to contribute positively by adopting proactive measures such as reformulating products, promoting food security, and adopting sustainable practices. By aligning their business models with health and sustainability goals, industries can play a vital role in mitigating these challenges and creating a healthier and more sustainable future (22).

There are some potential positive impacts that can arise from trade agreements that address commercial determinants of health. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) have been linked to positive health outcomes, with NAFTA reducing commodity prices in Mexico by up to 50% and boosting life expectancy from 72.4 years in 1994 to 76.7 years in 2014, while the USA's exports to Chile skyrocketed by over 500% after an FTA in 2004. Moreover, increased economic growth and trade volume from FTAs have contributed to enhanced healthcare spending and increased welfare, reducing inequality and almost eliminating poverty in certain regions (23).

There is a shift towards renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change. This also includes nuclear power that, as of 2021, contributes to about 10% of the world's electrical power (24) Although nuclear power possesses the potential to cause significant devastation as a weapon, the likelihood of a nuclear catastrophe occurring is comparatively minimal (25). Geopolitical cooperation and investment in these technologies can facilitate their adoption and deployment. For example, the International Solar Alliance, a coalition of more than 120 countries led by India, aims to increase the use of solar energy and reduce the cost of solar power in member countries. (26). A nationwide transition to electric vehicles (EVs) in the United States could lead to significant health benefits, according to a report by the American Lung Association. The report suggests that replacing gasoline vehicles with zero-emission vehicles could prevent 110,000 premature deaths, avert 2.8 million asthma attacks, and eliminate 13.4 million sick days by 2050, alongside a 92% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. This transition could result in public health cost savings of $1.2 trillion over the next three decades (27).

The growing influence of non-state actors, specifically philanthrocapitalists and philanthropic foundations, is undeniable in the realm of national and global health governance. These actors hold significant power to shape the world health agenda through substantial funding and transnational networks. In fact, certain foundations possess budgets that exceed those of certain nations and even the World Health Organization (WHO). Furthermore, there are concerns of imbalance in global governance decision-making and undermining of multilateralism through increasing private sector representation on global health partnership boards and various multistakeholder initiatives (28). Examples of action and strategies by governments and civil society to address the capture of global governance by corporates and their foundations, will be presented.

It is also important to note that a comprehensive approach to addressing CDoH would require structural reforms beyond action on specific corporations. For example, in the case of promoting breastfeeding, ensuring that parents have access to adequate maternal or paternal leave and quality care services is necessary, as well as increasing public financing and addressing the misalignment between private and public interests (29).

There are some civil society alliances trying to balance and deal with perceived crucial issues. One such organization is NCD alliance founded in 2009 with a robust global network of more than 2,000 organisations in 170 countries to combat NCDs. There are also the Global Alliance for Tobacco Control (GATC), whose mission is to unite and serve as the voice of civil society to accelerate implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), while integrating tobacco control in the global health and development agendas. For the planetary health, the Planetary Health Alliance has a mission to promote, mobilize, and lead an inclusive, trans disciplinary field of Planetary Health and its diverse science, stories, solutions, and communities to achieve the Great Transition, a comprehensive shift in how human beings interact with each other and Nature. There is also the Peace Alliance whose mission is to educate, advocate, and mobilize people into action to transform systems and public policy toward a culture of peace.

Social movements can advocate in the interests of grassroots and LMICs. For example, the People’s Health Movement (PHM) is a global network bringing together grassroots health activists, civil society organizations (CSO) and academic institutions from around 70 countries, particularly from low-and middle-income countries (L&MIC) to work on Comprehensive Primary Health Care and addressing the Social, Environmental and Economic Determinants of Health. The youth movement in social participation is a driving force in this 21st century. The Youth Alliance for Environment's (YAE), for example, demonstrated social participation through their proactive involvement in environmental conflict resolution, violence prevention, and empowering local communities with the necessary skills to address grassroots level conflicts in Kathmandu valley.

Health promotion is a valuable approach to address the negative impacts of commercial determinants of health. One way to utilize health promotion for this purpose is by increasing awareness and education about the negative impacts of CDoH, such as unhealthy food marketing, and educating individuals and communities on how to make healthier choices. For example, the C40 Food Systems Network supports cities to reduce carbon emissions and promote healthier, more sustainable diets. Cities like Copenhagen have developed food policies that prioritize plant-based foods, which are typically lower in carbon emissions and can contribute to healthier diets (30). Another strategy is to create supportive environments that promote healthy behaviors, like increasing access to healthy foods and creating safe and walkable neighborhoods that encourage physical activity. Advocacy for policy change is another effective health promotion strategy to reduce the negative impacts of commercial determinants of health. This involves advocating for policies that promote healthy behaviors and limit unhealthy behaviors, such as increasing access to healthy foods or limiting unhealthy food marketing to children. Additionally, working with stakeholders, including policymakers, businesses, and community organizations, to develop and implement solutions can be an effective way to address these negative impacts. Finally, health promotion can empower individuals and communities to take action to improve their own health and advocate for change in their environments. Health promotion is a powerful tool for counteracting the negative impacts of commercial determinants of health.

To achieve expected health outcomes, it is essential not only to form alliances at a global level but also garner support at the national level. This is where health councils/assemblies come into play, consisting of a diverse range of individuals such as CSOs, academics, service providers, and government officials. These councils have been developed in countries such as Brazil (1988), Thailand (2008), and Iran (2017), to serve as an additional tool to enhance the arena of health governance. By bringing together a variety of perspectives and expertise, these councils aim to improve the overall health system, ultimately benefiting the general population. (31). The way forward is then to discuss whether these present movements are enough or what else we need to gear the global governance for health in such a way we dream of.

Objectives

- To investigate the covert actors and forces shaping the impact of commercial determinants on global health

- To explore the interconnectedness between geopolitical dynamics and the influences of hidden actors on global health through commercial determinants

- To discuss the ethical implications of hidden actors’ involvement in shaping commercial determinants and their impact on vulnerable populations.

- To assess the role of regulatory frameworks in monitoring and addressing the influence of hidden actors on global health through commercial determinants.

- To propose policy recommendations and interventions to increase transparency and accountability in relation to hidden actors’ influence on global health via commercial determinants.

- Kickbusch, I., Allen, L. and Franz, C. (2016) ‘The commercial determinants of health’, The Lancet Global Health, 4(12). doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(16)30217-0.

- Gilmore A., Fabbri A., Baum F. et al. (2023) Defining and conceptualizing the commercial determinants of health. In Lancet series on commercial determinants of health. The Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2

- Mialon M. An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Globalization and health. 2020;16(1):74

- Ghebreyesus, T. A. (2023). Achieving health for all requires action on the economic and commercial determinants of health. In Lancet series on commercial determinants of health. The Lancet ttps://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00574-3

- Ottersen, O.P. et al. (2014) ‘The political origins of Health Inequity: Prospects for change’, The Lancet, 383(9917), pp. 630–667. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62407-1.

- Gopinathan, U. et al. (2014) ‘The political origins of health inequity: The perspective of the youth commission on global governance for health’, The Lancet, 383(9917). doi:10.10...6/s0140-6736(14)60050-7.

- Willett, W. et al. (2019) ‘Food in the anthropocene: The eat–lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems’, The Lancet, 393(10170), pp. 447–492. doi:10.10...6/s0140-6736(18)31788-4.

- Maani, N. (2018). Commercial determinants of health: A call for government action. World Medical & Health Policy, 10(1), 49-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.250

- Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Hatchard JL, Gilmore AB. Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: a review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK government consultation on standardized packaging. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001629.

- Supran G, Rahmstorf S, Oreskes N. Assessing ExxonMobil's global warming projections. Science. 2023 Jan 13;379(6628):eabk0063. doi: 10.1126/science.abk0063. Epub 2023 Dec 16. PMID: 36634176.

- Mialon, M., Corvalan, C., Cediel, G. et al. Food industry political practices in Chile: “the economy has always been the main concern”. Global Health 16, 107 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00638-4

- Van der Eijk Y, Bero LA, Malone RE. Philip Morris International-funded 'Foundation for a Smoke-Free World': analyzing its claims of independence. Tob Control. 2019 Nov;28(6):712-718. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054278. Epub 2018 Sep 21. PMID: 30242044.

- Posted on January 21, 2022 in Alcohol Industry (2022) Big Alcohol attempts to undermine WHO global action plan, Movendi International. Available at: https://movendi.ngo/media-release/big-alcohol-attempts-to-undermine-who-global-action-plan/ (Accessed: 11 September 2023).

- Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S., & Oreskes, N. (2023). Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science, 379(6628), eabk0063.

- Aaron M. McCright & Riley E. Dunlap (2011) The Politicization of Climate Change and Polarization in the American Public's Views of Global Warming, 2001–2010, The Sociological Quarterly, 52:2, 155-194, DOI: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

- Megan A. Brown, J.N. et al. (2023) The geopolitics of AI and the rise of Digital Sovereignty, Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-geopolitics-of-ai-and-the-rise-of-digital-sovereignty/ (Accessed: 07 August 2023).

- Schwalbe, N. and Wahl, B. (2020) ‘Artificial Intelligence and the future of Global Health’, The Lancet, 395(10236), pp. 1579–1586. doi:10.10...6/s0140-6736(20)30226-9.

- Schilling, J., et al. (2016). Syria: Climate Change, Drought and Social Unrest. Weather, Climate, and Society, 8(4), 397-417.

- Financial Times. “Russia’s energy conflict with Europe is turning attritional.” Financial Times, 9 Mar. 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/cde8696f-3c48-4f40-8599-79626b903591

- Larson, N. I., Story, M. T., & Nelson, M. C. (2009). Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(1), 74-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025

- Sallis, J. F., Spoon, C., Cavill, N., Engelberg, J. K., Gebel, K., Parker, M., ... & Floyd, M. F. (2016). Co-benefits of designing communities for active living: An exploration of literature. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 13(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0422-4

- Swinburn, B.A. et al. (2019) ‘The Global Syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission Report’, The Lancet, 393(10173), pp. 791–846. doi:10.10...6/s0140-6736(18)32822-8.

- Tasmim, S. (2019) ‘Free Trade Agreements and the Resulting Health Outcomes: Trade Flow, Knowledge Spillover and Government Regulations among Developing Countries’. https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3135&context=etd (Accessed: 27 July 2023).

- N/A (2023) Javascript required!, Nuclear Power Today | Nuclear Energy - World Nuclear Association. Available at: https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/nuclear-power-in-the-world-today.aspx (Accessed: 05 July 2023)..

- Igini, M. (2023). The advantages and disadvantages of nuclear energy. Earth.Org. https://earth.org/the-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-nuclear-energy/ (Accessed: 19 July 2023).

- International Solar Alliance. (2021). About ISA.)

- Lakhani, N. (2022) US transition to electric vehicles would save over 100,000 lives by 2050 – study, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/mar/30/us-electric-vehicles-save-lives-public-health-costs-study (Accessed: 05 July 2023).

- Blunt, G. D. (2022). The Gates Foundation, global health and domination: a republican critique of transnational philanthropy. International Affairs, 98(6), 2039-2056.

- Baker, P., Smith, J. P., Garde, A., Grummer-Strawn, L. M., Wood, B., Sen, G., ... & McCoy, D. (2023). The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress. The Lancet.

- N/A (2023) A global network of mayors taking urgent climate action, C40 Cities. Available at: https://www.c40.org/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwnf-kBhCnARIsAFlg490CEeLsXfwq1AAhMJqBjK0dvhdAVCNTWxS-fE9eIFnYHzKL0qXLVSgaAhdREALw_wcB (Accessed: 05 July 2023).

- Nanoot Mathurapote and Weerasak Putthasri. (2018). Global health disruptors: The rise of civil society. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/11/28/global-health-disruptors-the-rise-of-civil-society/

- IPCC Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. (n.d.). IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

Sub-theme 2 aims to discuss a way forward by exploring strategies and approaches that mitigate the harmful effects of CDoH on health and instead channel their influence towards promoting fairness, equality, and the overall well-being of individuals and the planet. This requires considering geopolitical considerations and developing policies and interventions that reshape the commercial sector's practices to prioritize health and social equity. The future directions should emphasize the need for a multi-faceted approach that addresses the complex and interconnected factors that contribute to commercial determinants of health. The governments should regulate and limit commercial practices that harm public health, support practices that promote health, and promote health literacy and consumer awareness. Additionally, the need to address commercial determinants of health in conjunction with social determinants of health and promote health equity is crucial (Maani, 2018).

Plenary 2 will identify hidden entities influencing global health, such as multinational corporation and lobbyists. The parallel sessions will subsequently explore these for four specific themes/industries – 1) food, beverage and agricultural industry; 2) energy producing industries; 3) “new” technologies; and 4) the pharmaceutical and medical devices industry.This discussion also highlights the ethical implications of these actors' influence, including health disparities and environmental harm. It will pinpoint gaps in current legislation, suggesting improvements for regulatory frameworks. By fostering public discourse, this dialogue enhances accountability, motivates responsible practices among these hidden actors, and raises public awareness about CDoH. Key actions are as follows:

- To investigate the covert actors and forces shaping the impact of commercial determinants on global health

- To explore the interconnectedness between geopolitical dynamics and the influences of hidden actors on global health through commercial determinants

- To discuss the ethical implications of hidden actors’ involvement in shaping commercial determinants and their impact on vulnerable populations.

- To assess the role of regulatory frameworks in monitoring and addressing the influence of hidden actors on global health through commercial determinants.

- To propose policy recommendations and interventions to increase transparency and accountability in relation to hidden actors’ influence on global health via commercial determinants.

References

- Friel S., Collin J., Daube M. et al. "Commercial determinants of health: future directions." The Lancet 401.10383 (2023): 1229-1240.

- Ghebreyesus, T. A. (2023). Achieving health for all requires action on the economic and commercial determinants of health. In Lancet series on commercial determinants of health. The Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00574-3

- Gilmore A., Fabbri A., Baum F. et al. (2023). Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. In Lancet series on commercial determinants of health. The Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2

- IPCC Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. (n.d.). IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

- Kickbusch, I., Allen, L. and Franz, C. (2016) "The commercial determinants of health.", The Lancet Global Health, 4(12).

- Maani, N. (2018). Commercial determinants of health: A call for government action. World Medical & Health Policy, 10(1), 49-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.250

- Mialon M. (2020). An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Globalization and health. 2020;16(1):74

- Willett W., Rockström J., Loken B. et al. (2019) "Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems." The lancet 393.10170 (2019): 447-492.

Biosketch

Bungon Ritthipakdee

Dan Smith

Lawrence O. Gostin

Monika Kosinska

Nason Maani

Pipit Aneaknithi

Session Materials

PMAC 2024 PL2.docx